All We Imagine as Dark

an analysis on "Veedu", one of the only dark-skinned female castings in Tamil cinematic history

On the bustling streets of Mumbai lives a contender from India for Best International Feature Film at the Oscars. Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light is a slice of two women’s lives who reckon with their city as they uncover the depths of its strike and ugly.

This was one of the first times I’ve seen dark-skinned women on screen speaking a Dravidian tongue. I will say it was alarming. But the best often happens that way.

Tamil cinema in particular has a distaste for the un-white. It isn’t sad really. I don’t know any different. But the realization has been steeping in me like that of a tea bag: disseminating and extracted when wrung heavy.

Until I watched All We Imagine as Light, I hadn’t named the quiet ache (I would name her Nirmala I think – old and familiar). To be watched and seen -- and seen as beautiful.

We talk about colorism as a deep, rotting wound, yet the Indian film industry punctures it daily and watches it throb. It is reopened with every malign omission and sutured with cheap yarn.

Of course, my mother saves me from peril. Thank God!

Over a stove top and burning fruit,

she told me about Veedu1.

“It is an old tamil movie” she said.

“Balu took it. He loved women who looked like you.”

It was a simple story: of a woman who wanted to build a home.

Middle class, navigating corruption and despair, and trying to keep everyone happy while holding onto a dream, she was at the whims of those who played with her money.

At its helm was the tragedy of being ordinary.

A resistance that suckled a clogged tit.

I watched the film with an untold swiftness and purgatory. Was I supposed to want this now? How horrid.

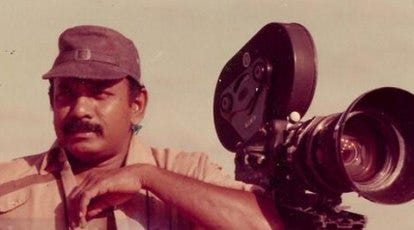

Directed and DP-ed by Balu Mahendra in 1987—a man who saw beauty in dark skin and framed it as such, Veedu portrayed dark-skinned women without the need to be softened, redeemed, or justified. They were not proxies for struggle, nor were they symbols of defiance. They were simply characters, with all the ideals that come with being as such.

There is much I would love to say about the disruption of this film, despite how harmful it was for my expectations. For what is art without the gluttony of self-insertion.

The Nature of Women

It’s ironic that the portrayal of women in their natural state, in their proverbial ‘veedu’s’ , is the most unbecoming version of them to Tamil cinema. Splain on cots with their hair worn down and corporealized into beings with agency, Tamil women have nothing more to give to the world beyond their “ordinary” for all else has been bartered out of them to be placed in fair-skinned forms

The protagonist, Sudha, of the film dug her heels into the notion of being without pretense. Sudha was far from a caricature of hardship or a supporting character but rather the heartstrings that chorded the movie.

Born into a middle-class family, Sudha’s dream was to build a house. She put her life savings into building a property from scratch, and the world unkind, she was cheated and scammed and cast as hostile for her desire. However, she was ardent, true, and stood up for herself time and time again against all odds.

Alongside Archana, the actress who played Sudha, was a cast of female characters that asked for things, charted discrepancy and unfairness with knives, and took care of one another without unneeded sacrifice. What I figured to be the most remarkable, however, was the undeniable vulnerability and softness of the women of Veedu. Round as whole fruit, Akhila Mahendra (Balu’s wife) wrote the screenplay for the film and preserved their fragility in their fission with strength – a duality that Tamil cinema often demarcates to the point of self-consumption.

Their femininity stood firm, woven into their strength without explanation – enduring in their deliberate and unapologetic emotional resilience.

So passionately themselves, the women of Veedu were champions of their own existence, and went after the noblest pursuit of all: to be ordinary and to be heard.

The Guy was Hot

Enough said.

It is actually not the norm in Tamil cinema right now to bring in new blood (honestly in all cinema nowadays). With a world full of nepos and lots of uggos, it was refreshing to see a beautiful woman end up with a beautiful man who supported her and loved her.

Did I mention too that they were “hanging”? Not in a relationship really, not married, just hanging. The first on-screen Tamil situationship, and I get it! Never seen a partnership this hot.

Akhila and Balu keep us fed.

Sisterly love

Seeing sisters on screen warms my heart. The original Edwina and Kate Sharmas (who were Tamil actresses playing North Indian heiresses mind you)!

It wasn’t common for women to be the forefront of any story, much less their relationships with one another. Sudha and her younger sister portray such a needed, tender, and honest version of siblings in Indian cinema that I find hard to see nowadays.

Class Divides

One of the most pivotal characters of the film comes halfway through in the form of a construction worker. Mangamma – bold, passionate, and divisive she is a construction worker who discovers the corruption on the site.

An iconic scene in the film pictures Sudha and Mangamma eating together in Mangamma’s hut – an attempt to reconcile caste divisions. Symbolic of what a “veedu” can entail, the hut houses the ambitions and care of both the characters as they sigh into their rice.

Cinematography

This film was brought to life by its room to breathe. Each scene a still life, Balu left moments behind for people to sit alone with the characters and scenes in the room.

He shot people like paintings and saw to it that we were arrested to our seats, placing us in environments we would be too impatient to relish in the digital age. Shot on handheld for the majority of the film, Balu too sat in these rooms and held a camera up to see what was truly inside each of their narratives. It is rare to see a director of photography in India perform that ritual nowadays.

No Noise in the Background

Not an ounce of music traced the background of this film. It was said that Balu saw these scenes as figments of his mother’s own struggle to build herself a house and how she became a shell of herself during it. The shell encases us as we participate in her deterioration through Archana.

For a film that speckled a landscape of extravagant dance sequences and flash mobs, Veedu forced the audience to reckon with the emotions and beauty that encompass a quiet story and give credence to the ordinary.

Commercial Flop

Okay, so this movie was a flop in the theaters, but I expected that.

People saw the film for the fact that there weren’t any big name actors or for a lack of a better explanation, they thought the story of a girl building a house was boring. It harbored no classic components of a good film at the time - a male lead, a light skinned heroine who gets pursued but is merely a manic pixie dream girl sexualized for her shyness, dance sequences, and a dramatic plot.

It’s departure from the norm rung highly amongst critics however, who viewed the piece as art of tall order. The film’s eschew of melodrama, and its instead focus on the subtle nuances of human relationships and bureaucratic hurdles brought it critical acclaim winning the Best Feature Film in Tamil award in the 35th National Film Awards and Archana winning the Best Actress Award.

They saw Balu’s panoramic scenes of daily life to be refreshing and understanding of cinema as a visual medium, and in 2013, leading journal Ananda Vikatan called Veedu “a film that took Tamil Cinema to a global stage”.

A Sign

I was watching this film in the living room, and my mom pointed to an actor on screen.

“Your grandpa and him were friends," she said.

He was owner of the house shown to Archana and her grandfather. The grandfather looked just like mine. He had the same gait and hair, had three granddaughters, and he signed away his money before his death.

I saw my grandfather buying property.

Perhaps home was closer than I thought.

My Takeaways

1. Seeing someone that looked like me in the eyes of a beholder was nice but horrible for managing expectations.

2. We need to reward directors who unseat harmful norms, and actually go to watch more Independent Indian Films (and watch them on reputable platforms so they get the recognition they deserve)

3. I’m convinced the resurgence of dark-skinned women on screen will happen via women (Shonda Rhimes, Payal Kapadia, Mindy Kaling, etc.). Some will be diasporic and some will fight national turmoil to bring these films to light.

All I can imagine is Not dark as of now, but in the future, I hope there is a world where I can not only imagine dark-skinned women speaking Tamil on screen but expect it.

House

omg i loved this!! the movie is def going on my watchlist + i loved the teabag metaphor, “gluttony of self insertion” and “tamil women have nothing more to give beyond their ordinary”