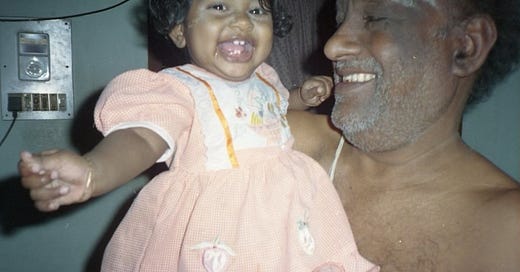

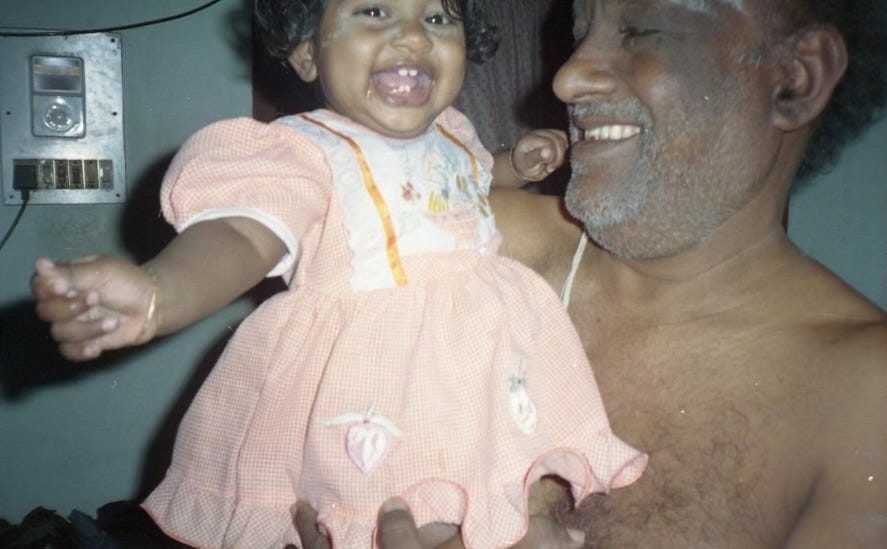

I’ve been having this recurring dream for the past few days. We (my Thatha1 and I) are walking down the street that leads to my uncle’s house. He is holding my hand, walking slow. I am behind him, but in his head, I walk beside him.

He guides me the courtyard behind our house, past the pavement and stone blocks, to a sliver of dirt anointed with trees whose branches touch his shoulders. Most of them bear fruit. The small one he tugs on definitely does. It’s black, deep, pitted. And it resembles a scarab of some sort almost. It has an overwhelmingly large seed that sprawls across the inner flesh.

We eat it together in silence.

He passes me another.

I spits the seeds into the soil.

My mother told me that she lost me in the middle of a Walmart once when I was five.

“You were nowhere to be seen, we almost announced your name on the loudspeaker but didn’t know how.” she said.

She said the vested worker found me in behind the book racks at the front of the store, back when there was just 2 spinning carousels holding children’s books. She yelled at me in front of the man, and I cried.

Later she told me that’s how she figured out I liked reading.

🛋️

My grandfather used to send me books when I was younger. He was a proprietor of my education, but more than anything he was a tiller of my habits. When I would awake in the morning, what I would do first after I got home from school, and mostly the words I would surround myself with were all of his concern.

He wanted me to be wise one day. He said he shaped my days so that wisdom would find me in the moments between them.

Books were his chosen vessel from abroad. Workbooks and storybooks in English, about English, about science, about the world, and what was beyond. They were packaged meticulously, each one bound with signature yellow covers. He bound them himself, sometimes to add in pages or hardbacks to avoid damage. His handiwork laid adroitly in the spines. They were so ordinary I thought they had always been that way. Only now, looking back, can I imagine him sitting on his balcony sewing those pages sheet by sheet and pasting the hardcover across the binding.

Packages from abroad were rarely spared the wrath of the ports. Yet his arrived as if they had slipped past the turmoil unnoticed - the packages maintained their tape and the books retained their diligent armor of Fevicol and the faint, familiar tinge of borax.

🪑

My grandfather visited the US for the first time when I was in 7th grade. I had a project about Native American tribes that martyred them - we were to make a book listing out their tribal characteristics. It wasn’t common in my house to involve my grandparents, and for that matter, my parents, in my work.

But he was in the living room, and I was too.

“Na help pannituma?2,”he asked.

I looked at him confused, wondering what he would even help with. Would it be the folding (I could do that myself) or the sticking pictures on the pages (I could do that on my own) or the handing it into the teacher (that would have to be me too)? He was fragile, so his art must be as well.

However, he asked again, and I obliged.

I was to bring him some materials: a glue stick, liquid glue, tape (double-sided), cardboard, a pair of scissors, and a sewing needle with a string already in the eye. Materials laid in front of him, he cut straight through my booklet slicing the pages into individual sheets. I grabbed it away from him.

“One minute, kanna3, fix paniren.4” he said.

He punctured soft holes throughout the edges and pulled the needle through them. Taking the ends of the strings, he formed little balls, knots of various sizes to secure the pages. He ripped the cardboard apart on its seams, and placed it on hem of the pages forming a spine.

Using scissors this time, he cut along the seam once again. It outfit the exterior, a finish ahead, my eyes darted across his handiwork.

He was not finished however.

Folding the sea of blue construction paper with his long fingers, he became a tailor. The inside folds glued. The book laid carefully to the side like a small child. He pulled the paper over her sleeves and soothed it over the top edge and bottom and handed me my book fully dressed.

I received it in disbelief.

How silly of me to not recognize him in the spine of my books.

How embarrassing of me to admit I had forgotten.

💡

I remember our trip to Higgenbothams. What a silly name! It’s a gigantic book store in the middle of Chennai named after an English stowaway, passerby always feel like they’re being watched by it and its oddly white presence.

Weird how the two places that remind me of my Thatha so pungently are British. Elliot’s Beach, where he hung to my sleeve as we dipped our feet in the water one afternoon, and an imposing book store.

We took the bus to Higgenbothams that day. First on autorickshaw then to the bus stop hand-in-hand. I was 15, but he felt safer that way knowing I was cared for. Before that day, I had no idea of Anna Nagar (where we were going) or Higgenbothams (why we were going) or the fact that my grandfather had some business in the area (what we were really going for but I couldn’t tell anyone). This was my second time riding the bus in India, and I didn’t know how to sit or who to give my seat to. It seemed a lot more selfish here with the crowd, standing up to give someone a place to sit was "too much” - you could hide behind the fact that it was at least.

I knew it when I saw it - the bleak white building with eyes. It was pretentious and alluring all the same, inside was no different. There were no shelves, just books donned onto rows and rows of tables covered in white cloth, laid down to rest almost.

We spent the afternoon unearthing the dead, scouring table after table searching for all but nothing. He told me about the books he bought for my mom.

“Anthaa Tom Sawyer paiyan pathi,5’ he said laughing.

I stumbled upon a slew of Amir Chitra Katha comics6.

“Vennuma?7” he asked.

I was unabashed and nodded.

We left the bookstore weighed down by the prospects of a ‘New Retelling of the Ramayana’ and stories of crows that could talk and teach lessons to children. The bus was twenty minutes late, but I didn’t mind. The bus stop was the perfect waiting room for beginnings of stories about crows teaching lessons to turtles.

The bus was boarded.

I was a turtle the whole ride back.

🪑

My Thatha passed this last January.

He was laid to rest under the same pretenses most Indian grandfathers and mothers take leave - an ailment given by the British in exchange for gold.

The last conversation I remember of his was about a tree that he wanted to show me in the backyard. I was tired and never saw it.

I went to Boston to see my friend, and we did a book tour around the city. I saw him more than ever. I knew that would happen, though.

He is in every book I’ve ever read. He made every single one of them.

🏩

My family and I went to eat at an Indian restaurant near my house, and I thought I saw someone that looked exactly like him.

“Let me take a look at the upstairs of this place,” my mom had said a second prior, leaving her bag with me. I could not be more grateful for her nature - God told her to hide.

He walks in a familiar gait with his hands behind his back, a familiar set of thick lenses with gold frames, and a familiar hat for the cold. He walked straight to a shallow red chair, and his veshti8 rode to his thighs.

I call to my dad who just walked in the door. He was sitting in the car before, waiting for a text saying our table was ready. Now he was here; the lady just called our name.

Tugging on my dad’s sweater girlishly, I whispered:

“I found someone that looks exactly like Thatha.”

He looked into the restaurant first, and asked me to repeat what I said - not in disbelief but in the split-minded way he always was.

“Come here,” I ushered.

“Look behind me,” I said standing in front of him.

He looked beyond my shoulder to my Thatha sitting in the shallow chair behind us.

He looked confused. “I don’t really think so, kanna,” he said laughing.

I still don’t know which one of us forgot.

🛏️

I am India now for the one year anniversary of my Thatha’s wake.

The ceremony is at my uncle’s house, and I see the tree now.

It looks different than my dream.

It’s saintly and pious, each leaf bowing to the reacher: the branches rudely race to the sky.

It is larger than I imagined, and the plot of land is bigger.

It doesn’t bear fruit, but it could.

Instead it beams with flowers.

I sit in front of it.

In my head, he is behind me.

Grandpa

Can I help?

Darling

One minute, I’ll fix it.

About that Tom Sawyer boy

A Popular Comic Book series in India

Do you want it?

Cloth worn around the waist as a skirt; commonly by men in India

You're incredible genuinely, this was so beautifully written!!